Winter outlook 2022

Large areas of Australia are likely to endure a cold and wet winter, with elevated potential for snowfall, frequent flooding and dangerous east coast lows.

Wet lead-up to winter

Much of Australia had a very wet start to 2022, with parts of every state and territory receiving above-average rain between January and May. The map below shows that some areas of central and eastern Australia have picked up more than two times their average January-to-May rainfall over the last five months.

Image: Rainfall percentages between January and May 2022. This map shows how much rainfall has fallen over the last five months as a percentage of the long-term-average for this period. Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

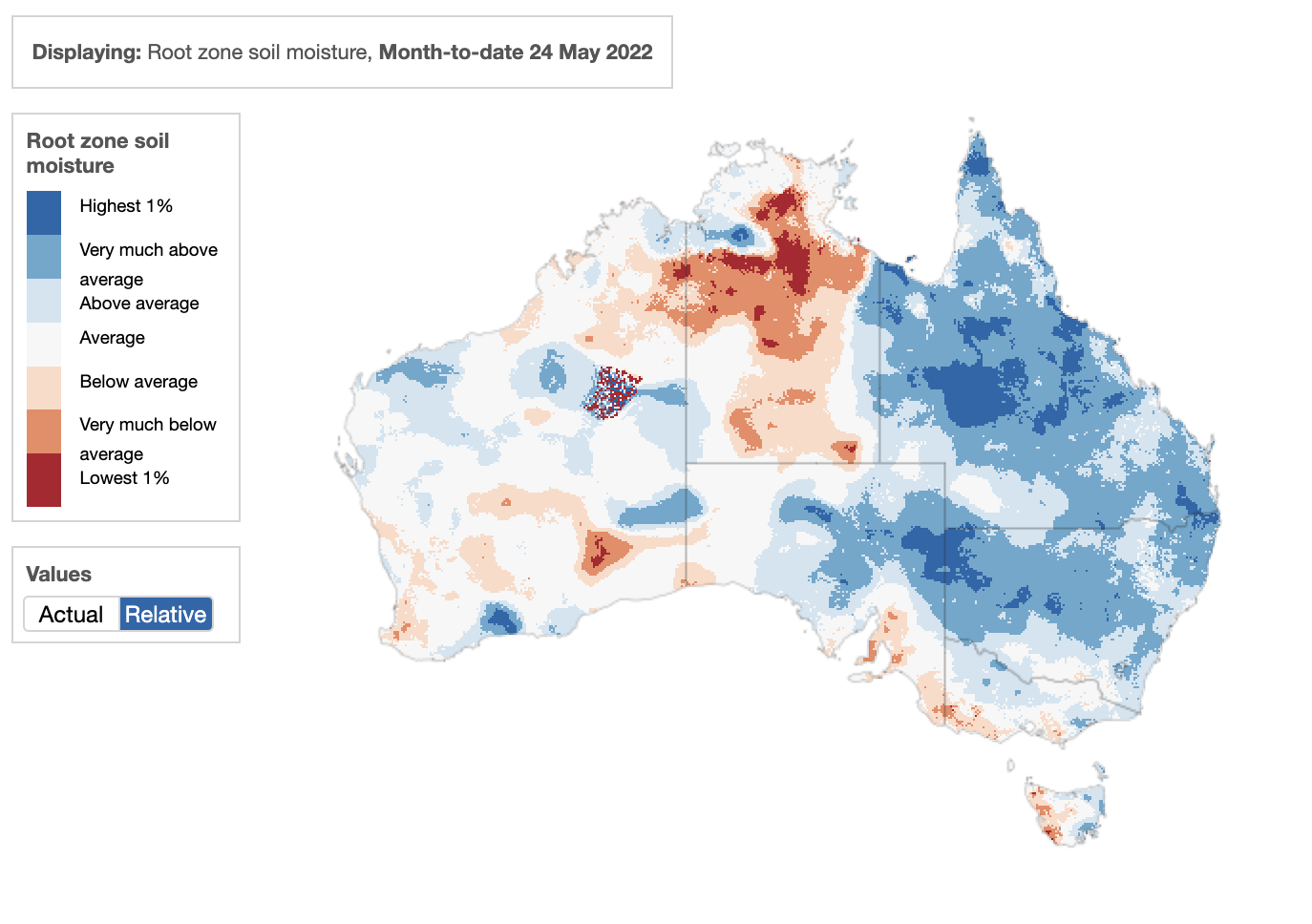

This rain has left above-average groundwater across a large swathe of the country, with rivers and dams bulging in some areas as we head into winter.

Image: Root zone soil moisture anomaly during May 2022. The blue areas show where soil moisture in the top one metre of the soil profile is above the long-term average for this time of year. Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

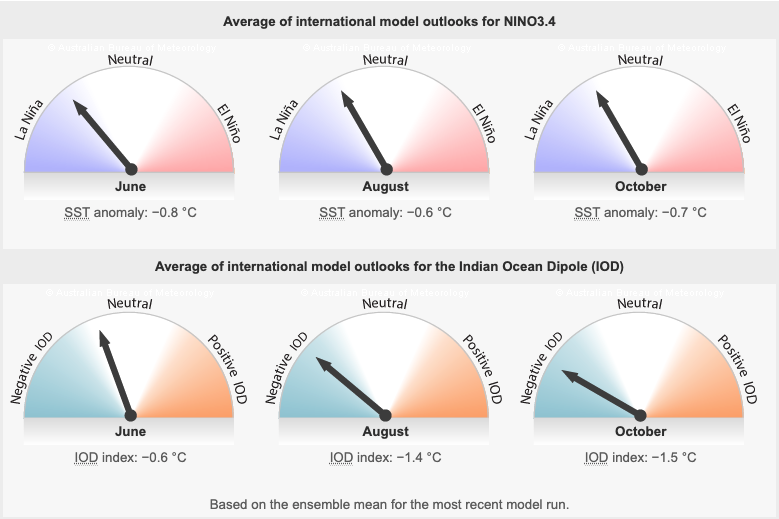

This year’s abundant rainfall has been underpinned by La Niña in the Pacific Ocean, which has been in place since late last year and is still lingering as we approach the end of May.

As Australia heads into winter, La Niña or a La Niña-like pattern is expected to persist in the Pacific Ocean. On the other side of the country, and a negative Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is also likely to develop in the coming weeks and should persist through winter and into spring.

Image: Predicted phases of ENSO (top) and the IOD (bottom) during June (left), August (middle) and October (right) this year. Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

La Niña and a negative IOD are both climate drivers that increase the likelihood of above-average rain and below-average daytime temperatures over large areas of Australia. They also influence snowfall, wind, fog and frost in Australia during winter.

Rainfall and flooding

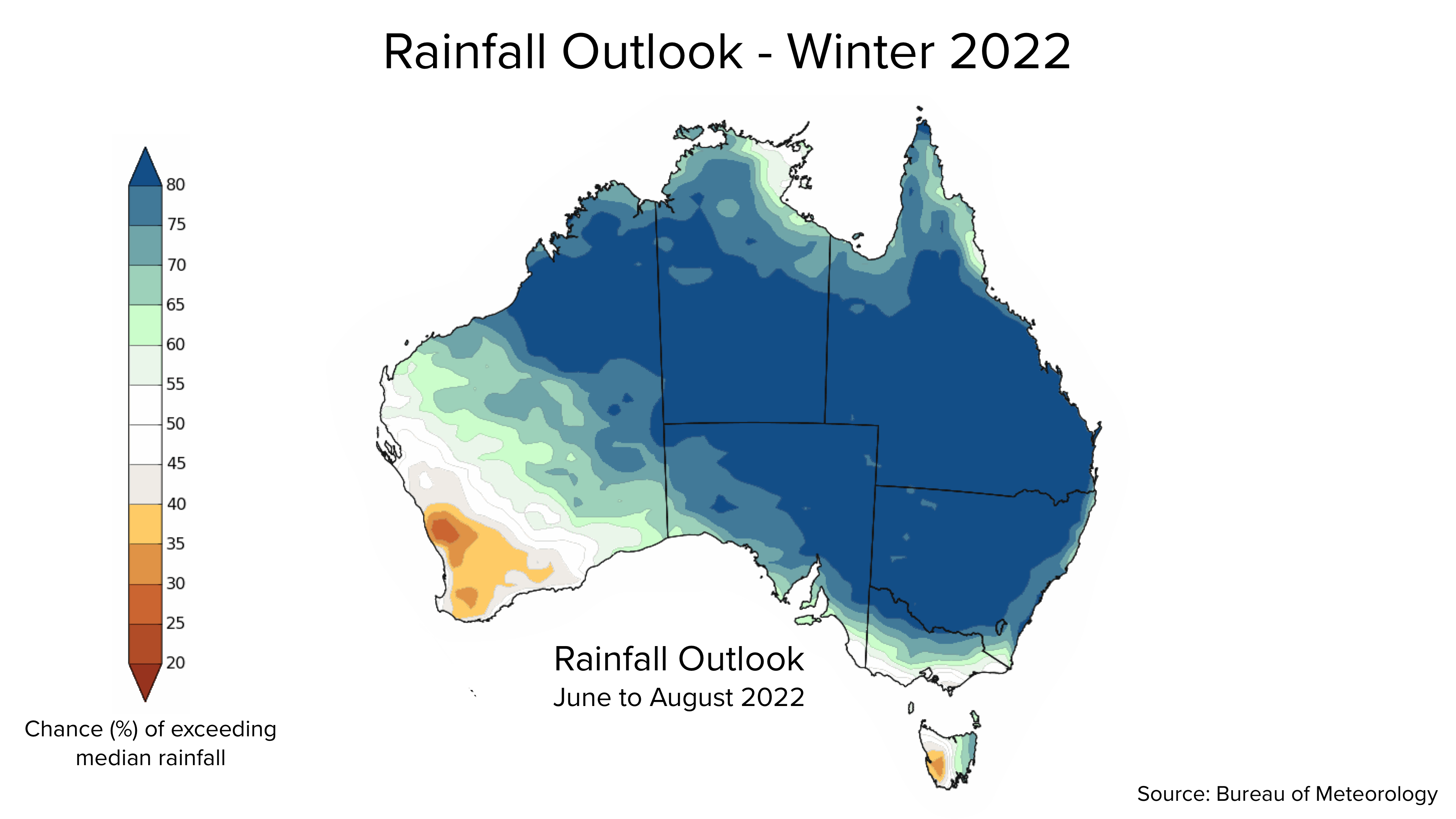

A negative IOD typically causes an increase in northwest cloudbands, which transport tropical moisture across Australia from the northwest and convert it to rainfall over the continent.

The lingering La Niña-like pattern should also help push moisture towards Australia from the Pacific Ocean, further increasing the likelihood of above average rain in the north and east of Australia this winter.

The combined influence of the negative IOD and La Niña-like pattern significantly increases the chance of an abnormally wet and cloudy winter for much of Australia.

Image: Chance of exceeding median rainfall during winter (June to August). Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

These two wet-phase climate drivers also increase the risk of flooding over northern, central, eastern, and southeastern Australia, especially in places that had a wet summer and autumn.

Warm sea surface temperatures surrounding Australia will also enhance rainfall in winter and can also enahnce thunderstorm activity near the coast.

Temperature

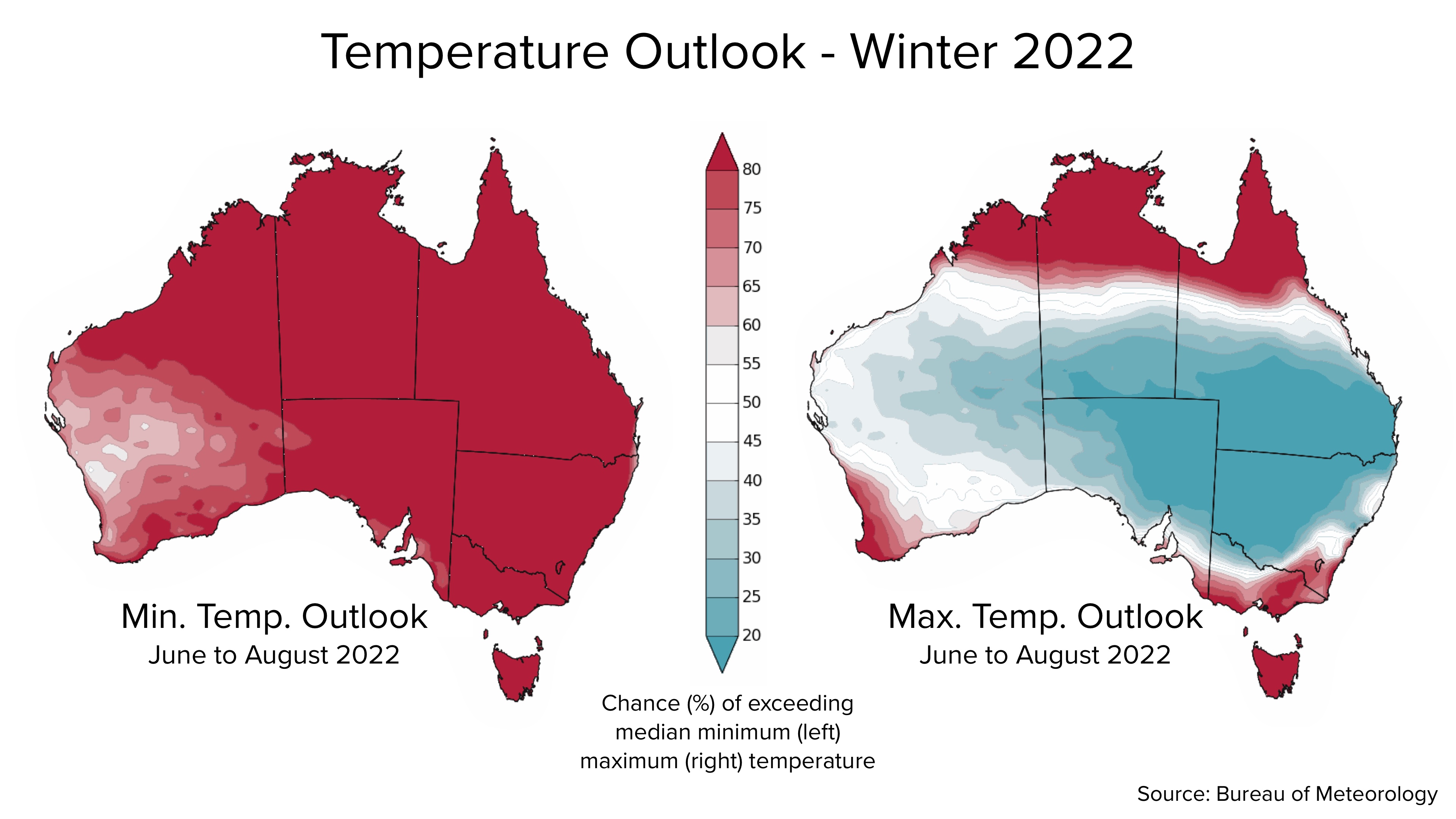

Increased cloud cover caused by the negative IOD and lingering La Niña-like pattern is likely to affect both maximum and minimum temperatures in Australia this winter.

Daytime temperatures are expected to be lower than average over much of central and eastern Australia and parts of southern Australia, particularly inland areas. However, days may be warmer-than-average in the north, far southeast and southwest, where the influence of La Niña and the IOD are weaker.

By contrast, overnight temperatures are likely to be warmer-than-average for most of Australia this winter, with increased cloud cover limiting overnight cooling.

Image: Chance of exceeding median minimum and maximum temperatures during winter (June to August). Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

Frost and fog

Abnormally warm and cloudy nights should reduce the overall frequency and intensity of frost this winter, particularly across inland areas of southeastern Australia. However, there will still be frosty nights and mornings during periods of clear skies.

Meanwhile, moisture from groundwater and rainfall is likely to help produce fog this winter during periods of clear skies between rain events.

Snow

Seasonal snow depths in Australia are notoriously fickle and difficult to predict. However, climate drivers can influence seasonal snow depths in the Alpine regions.

La Niña and a negative IOD both increase the amount of moisture in the atmosphere over southeastern Australia. However, moisture is only one of the key ingredients needed for good snow. The other is below-freezing temperatures.

Recent studies have found that Australia’s Alpine snowpack is generally deeper during negative IOD years. There is also a strong correlation between Australian snow depth and the Southern Annular Mode (SAM), with seasons dominated by negative SAM typically yielding more snow.

The SAM simply refers to the north-south displacement of a belt of westerly winds that flow between Australia and Antarctica. When the SAM is negative, these westerlies are located further north than usual, which can cause cold fronts to become stronger and more frequent over southern Australia in winter. Unfortunately, the SAM can’t be predicted beyond about the next two weeks.

So, while there is potential for a bumper snow season this year thanks to the negative IOD and La Niña-like conditions, the difference between this season being a boom or a bust will come down to the strength and frequency of cold fronts.

Wind

Like snow, wind in southern Australia during winter is strongly correlated with the SAM, with periods of negative SAM typically causing stronger-than-average winds and positive SAM bringing lighter winds.

While predicting SAM is generally limited to the next one to two weeks, La Niña is usually associated with more positive phases of the SAM. If we do see a La Niña-like pattern persisting in the Pacific Ocean in the coming months, this would increase the likelihood of weaker and less frequent cold fronts in southern Australia.

However, it La Niña breaks down and the Pacific Ocean returns to neutral, there are no remaining indications that wind will be stronger or weaker than average this winter.

East Coast Lows

Early-to-mid winter is the peak season for East Coast Lows in Australia. These high-impact low pressure systems pose a risk of causing more flooding and coastal erosion over Australia’s eastern seaboard this winter, especially in areas of eastern NSW and southeast QLD that saw major flooding in late-summer and autumn.

While it is difficult to predict East Coast Low numbers for each season, warm sea surface temperatures are a key ingredient for their formation. With water temperatures currently 2 to 3ºC warmer than average in parts of the Tasman Sea, this may help with East Coast Low development in the coming weeks.

Climate Change Influence

In addition to the state of the main climate drivers surrounding Australia, the background influence of climate change is also affecting Australia’s weather during winter.

Cool season rainfall has been declining over large areas of southeastern and southwestern Australia in recent decades. The map below shows the rainfall deciles between April and October during the 20-year period from 2000 to 2019, compared to the long-term average (1900 to 2019). Orange shading shows areas that have been drier than average between April and October over these two decades.

_1.png)

Image: Observed April-to-October rainfall deciles for the 20-year period between 2000 and 2019, relative to the long-term average of the entire rainfall record (1900 to 2019). Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

Winters have also been getting warmer for most areas of Australia in recent decades, with Australia’s national average maximum temperature in winter increasing by just over 1.5ºC since 1910.

Image: Observed trend of Australia’s average winter maximum temperature between 1970 and 2021. Source: Bureau of Meteorology.

This warming trend, combined with reduced rainfall, has also had a negative impact on Australia’s snow season, by reducing the average length and peak snow depth of the season.

Summary

Much of Australia is likely to see above-average rainfall this winter, driven by a strong negative IOD and lingering La Niña-like pattern in the Pacific Ocean. This rain will increase the risk of flooding in areas that have entered winter with above-average groundwater concentrations.

These climate drivers should also enhance cloud cover over Australia, making days cooler and nights warmer for large parts of the country. Cloud should also limit the development of frost and fog this season, although both phenomena will still occur on a regular basis.

Snowfall has the potential to be above-average in Australia this winter, as long as temperatures aren’t too warm when rain-bearing cold fronts arrive in the Alps. This will be influenced by the prevailing phase of the SAM as the season unfolds.

An abnormally warm Tasman Sea could help fuel the development of East Coast Lows, which bring a risk of further high-impact weather events along Australia’s flood-weary eastern seaboard this winter.