When is a cyclone not a "cyclone"?

Here in Australia, when we hear the word “cyclone” we tend to think of tropical cyclones. But did you know that cyclones also occur further south than the tropics?

Technically speaking, a cyclone is any weather system in which winds rotate inward toward a region of low pressure. Conversely, an anticyclone is any weather system in which winds rotate outward from a region of high pressure.

Sometimes, cyclonic systems can have quite intense or severe impacts, like destructive winds or heavy rainfall. When we think of those types of intense cyclonic systems, we usually think of tropical cyclones like Cyclone Tracy, a severe tropical cyclone that smashed into Darwin in 1974, or Cyclone Yasi, another severe tropical cyclone that barrelled into northern Queensland in 2011. These systems tend to form in tropical regions (between around 5° and 30° latitude from the equator), which is what gives them their name. But intense cyclonic systems can also occur in the mid-latitudes (between around 30° and 60° latitude from the equator).

Earlier this week, a trough off the southeastern Qld and northeastern NSW coast developed into a low pressure system, which you may remember brought a month’s worth of rain to the Gold Coast, something Weatherzone meteorologist Ben Domensino reported on this Tuesday: https://www.weatherzone.com.au/news/one-months-rain-soaks-gold-coast-overnight/1273377

That system developed into what’s known as an “extratropical cyclone”, which has been wreaking havoc over New Zealand’s North Island today, delivering heavy rainfall and gale force winds in some areas. The same system also delivered a large southwesterly swell with some damaging surf conditions to Norfolk Island’s south coast today.

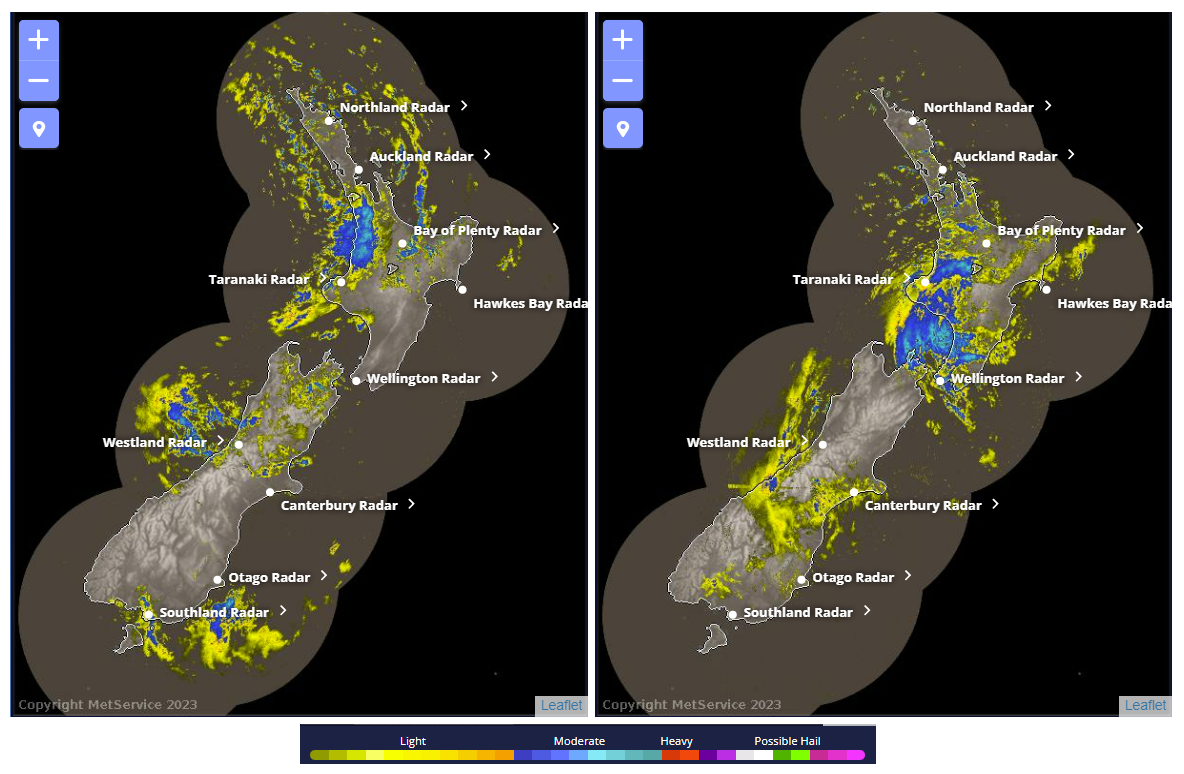

Left: New Zealand Met Service radar image at 4:58am NZST 20 May 2023. Right: New Zealand Met Service radar image from at 7:43pm NZST 20 May 2023.

So, what makes an extratropical cyclone different from a tropical cyclone?

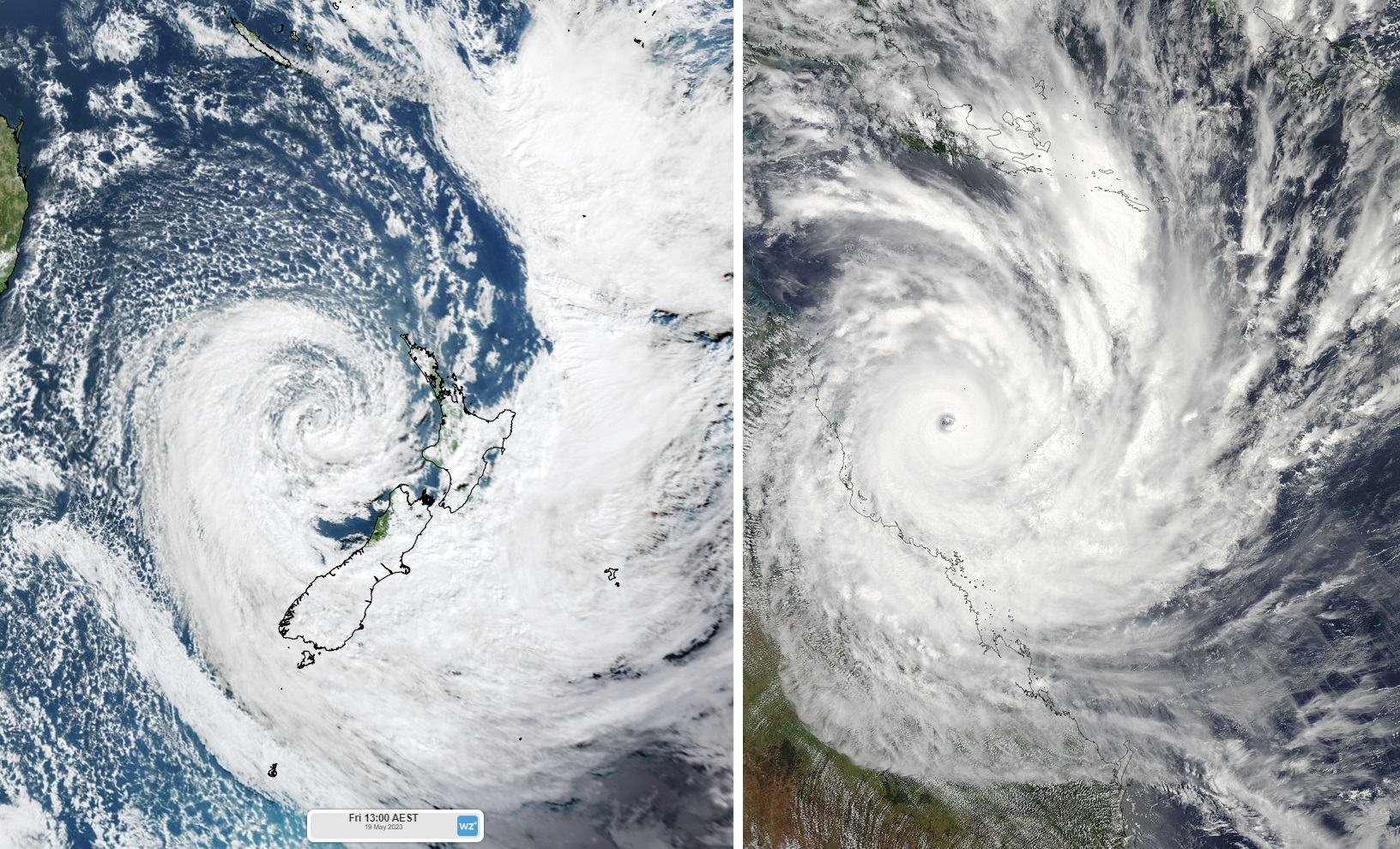

Take a look at the shape of the extratropical cyclone as it headed toward New Zealand yesterday and compare it with the shape of Severe Tropical Cyclone Yasi back in 2011:

Left: Visible true colour Himawari satellite image taken from Weatherzone’s GIS Viewer on 19 May 2023, 1pm AEST. Right: Visible true colour satellite image of Cyclone Yasi (source: NASA Goddard MODIS Rapid Response Team)

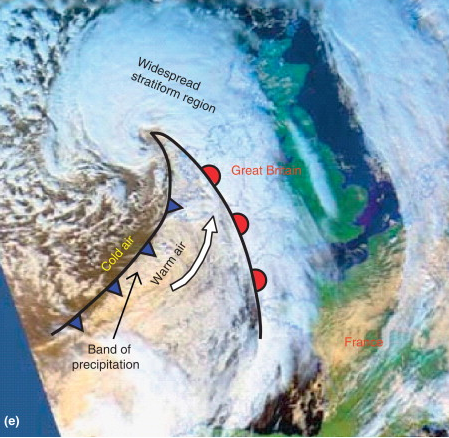

Notice anything? The extratropical cyclone near New Zealand has a kind of backwards comma shape with one main cloud “arm” while Cyclone Yasi has a spiral shape with several cloud bands. Since tropical cyclones form in the tropics, where there is little difference in horizontal temperatures, they have no discernible fronts, giving them their characteristic spiral shape. Extratropical cyclones, on the other hand, form in regions where there are often strong horizontal temperature differences, giving rise to a cold front and warm front, resulting in a kind of comma shape. In this comma shape, the warm front sits ahead of warm, moist air marked by thick cloud development. The cold front sits ahead of an influx of cold, dry air marked by a distinct lack of cloud cover in comparison. Here’s a frontal schematic from a similar extratropical cyclone over the British Isles in 2009.

Image: Schematic illustration of an extra-tropical cyclone over the British Isles on 17 January 2009. Source: D. Koutsoyiannis, A. Langousis, in Treatise on Water Science, 2011

A similar set of fronts can be seen in the Bureau's mean sea level pressure analysis map from yesterday:

Source: Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology

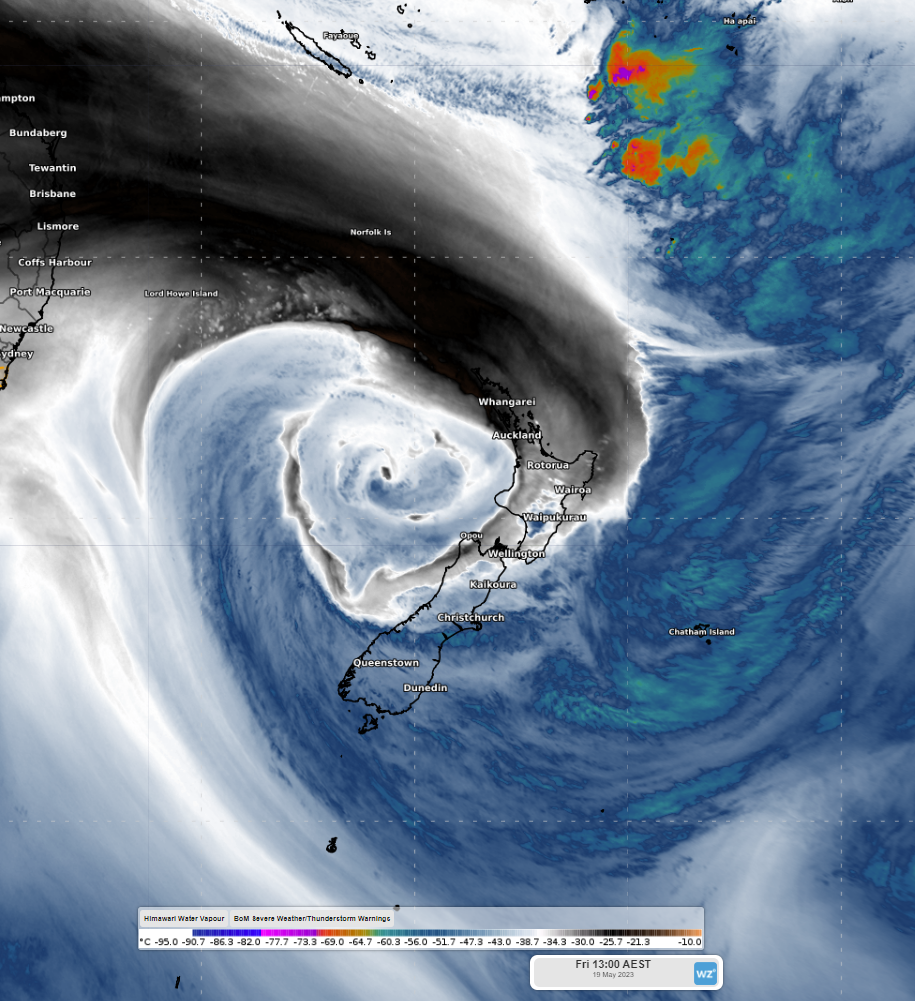

To further illustrate the differences in moisture, take a look at this water vapour image of the New Zealand extratropical cyclone below, taken at around the same time as the satellite image shown earlier. Black areas denote dry air, while blue to red areas denote high water vapour content.

Image: Water vapour over New Zealand, Friday 19 May 2023, 1pm AEST

This particular system is likely to continue to affect New Zealand’s North Island tonight and should shift eastward tomorrow, allowing for conditions to ease significantly. However, a second low pressure system seems likely to develop in the Tasman Sea early on Monday morning, which will bring further rain and gusty winds to New Zealand on Monday and into Tuesday morning.