Satellite imagery mystery revealed

Satellite images are full of captivating features that help revel the incredible dynamics of our planet's atmosphere. But clouds are not the only thing we can see using weather satellites, and one of the more mysterious phenomena can be seen on the animation below.

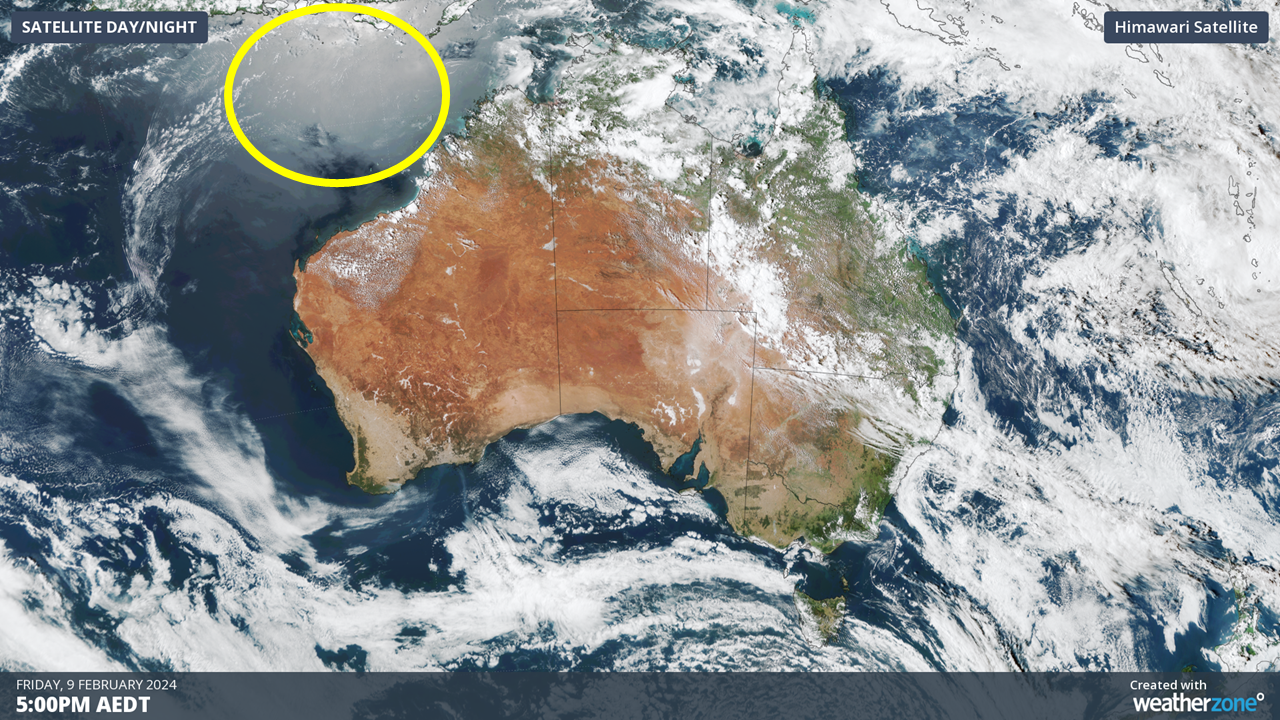

3-hour loop of satellite imagery from yesterday afternoon

What do you think that strange glow is moving across the oceans to the north of Australia? Is it the oceans heating and cooling during the day? No. Is it aliens flying by and scanning the Earth? Also no. The answer is incredibly simple. It is in fact, the reflection of the sun. Or what meteorologists and photographers refer to as ‘sun glint’.

Sun glint over the ocean off the northwest coast of Australia

At the end of the day, satellite photos are just photos (or more accurately, the result of electromagnetic waves within the visible spectrum hitting a detector on a geostationary satellite, about 36,000km above the Earth’s surface). And these photos are prone to many of the same issues that plague photographers. Have you ever tried to take a photo with a window, glass, or even a body of water in the background? Light reflecting from the sun can often ruin part of a photo. Well, it’s the same thing happening here. Light from the sun bounces off the ocean surface, directly into the camera, producing a bright spot on the ocean. As the sun moves from east to west as the day progresses, this bright spot also moves across the ocean to the west.

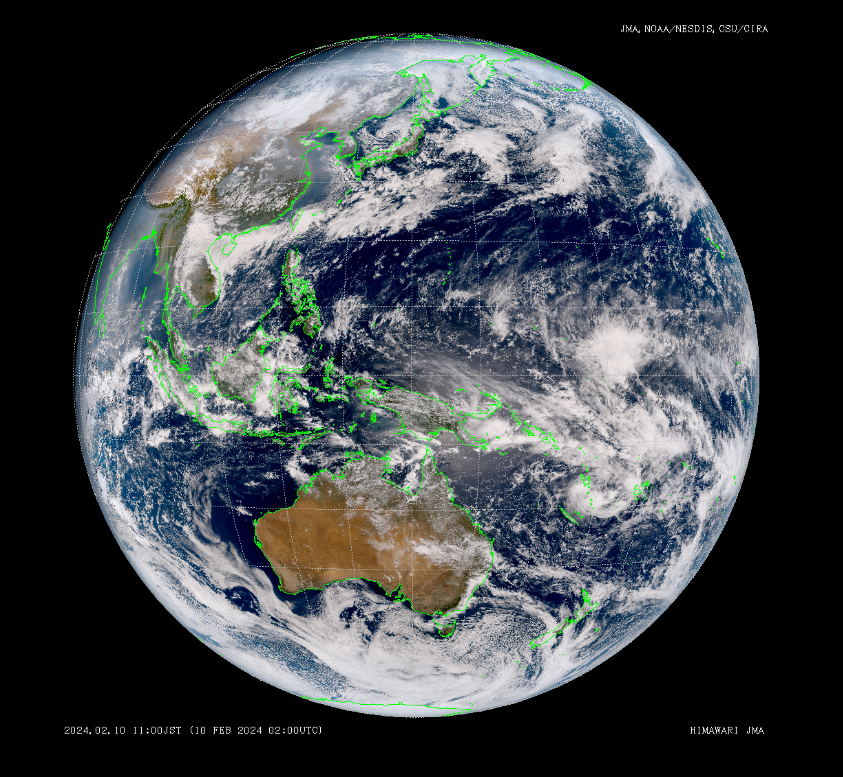

The full disk image is what the satellite really sees, completely zoomed out. This ‘true colour’ image is a combination of the 3 visual channels: red, green and blue. Source: JMA (Japan Meteorological Agency)

Satellite imagery (visual, infrared, water vapour and many others) is one of the key tools that meteorologists use to diagnose and predict the weather. When the current Japanese weather satellites Himawari 8 and 9 were launched almost a decade ago, for meteorologists, they were like upgrading from a Super Nintendo to a PlayStation 5. Resolution increased from 1-4km per pixel to 0.5-1km and the frequency of images increased from 30-60 minutes to one image every 10 minutes (in Japan, this can be increased to every 2.5 minutes for typhoons and severe thunderstorms). The ultra-crisp and ultra-smooth visuals helped us see many atmospheric processes and phenomena that we’d studied but never seen with our eyes. A decade later, I’m still mesmerised by loops of satellite images.

If you want to explore satellite imagery for yourself, check out the weatherzone page, or head to the source at the JMA (change Infrared to True Colour then pan down to Australia) for hours of fun.