Positive IOD possibly brewing in 2023

A positive Indian Ocean Dipole may be brewing this year, that would lead to a dry winter and spring in 2023. But how much faith should we have in this forecast?

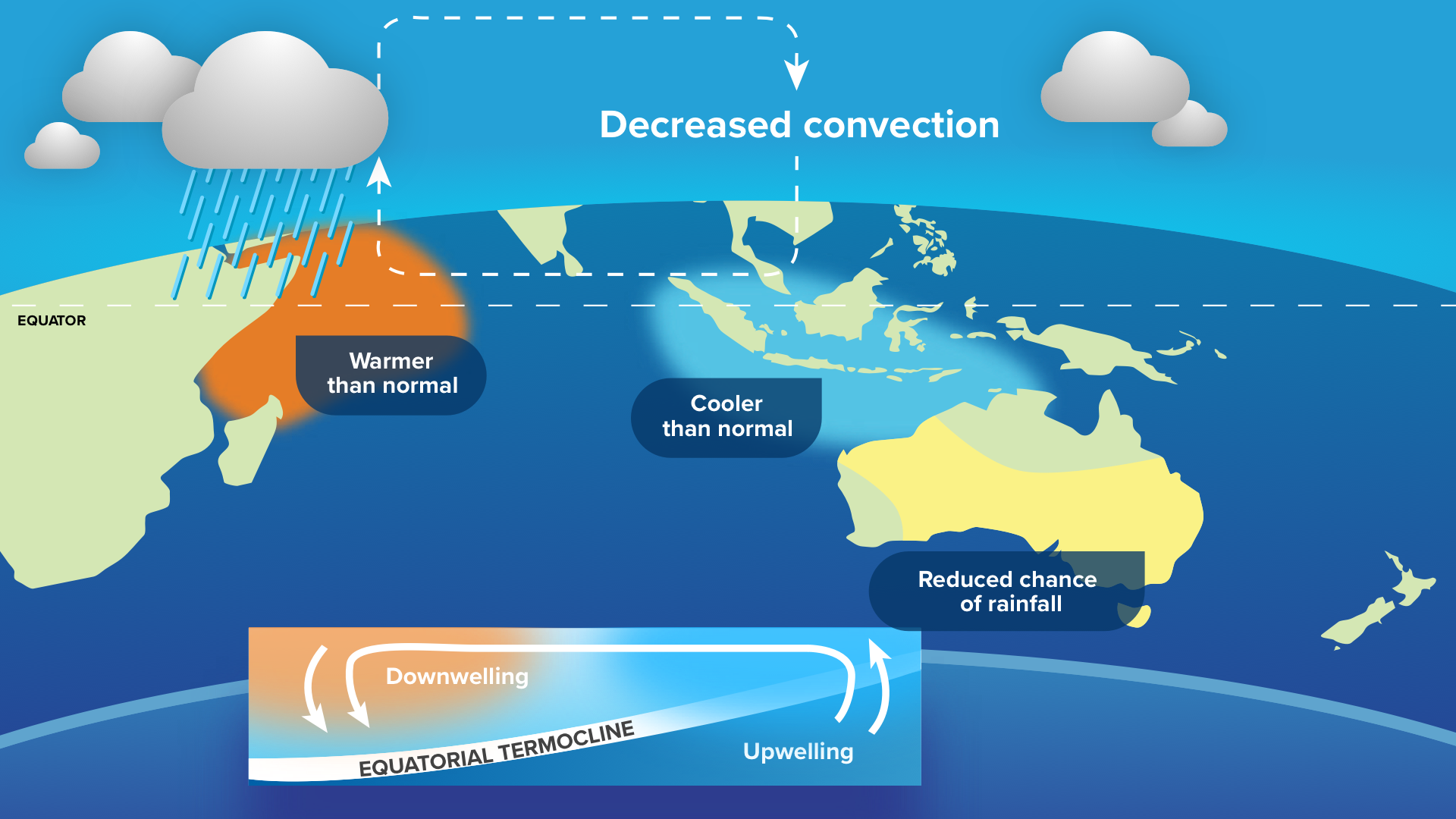

The Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) is a similar climate driver to El Niño and La Niña in the Pacific Ocean. It is based on the interaction of ocean temperatures and the atmosphere above it, leading to changes in rainfall and temperatures over Australia.

The IOD has its strongest effect on the weather during winter and spring, but unlike El Niño and La Niña, it becomes irrelevant during summer once the monsoon first arrives. The IOD can be in three states: positive, negative and neutral.

Negative IOD events push warm waters near Australia and cause air to rise in the nation’s northwest. The resulting weather usually comes in the form of a northwest cloudband, that delivers wet conditions across the country, but particularly to the southeast and inland.

Over the last two years, Australia has experienced two consecutive negative IODs (akin to La Niña). This was the first time since records began in 1960 that two consecutives negative IODs had occurred.

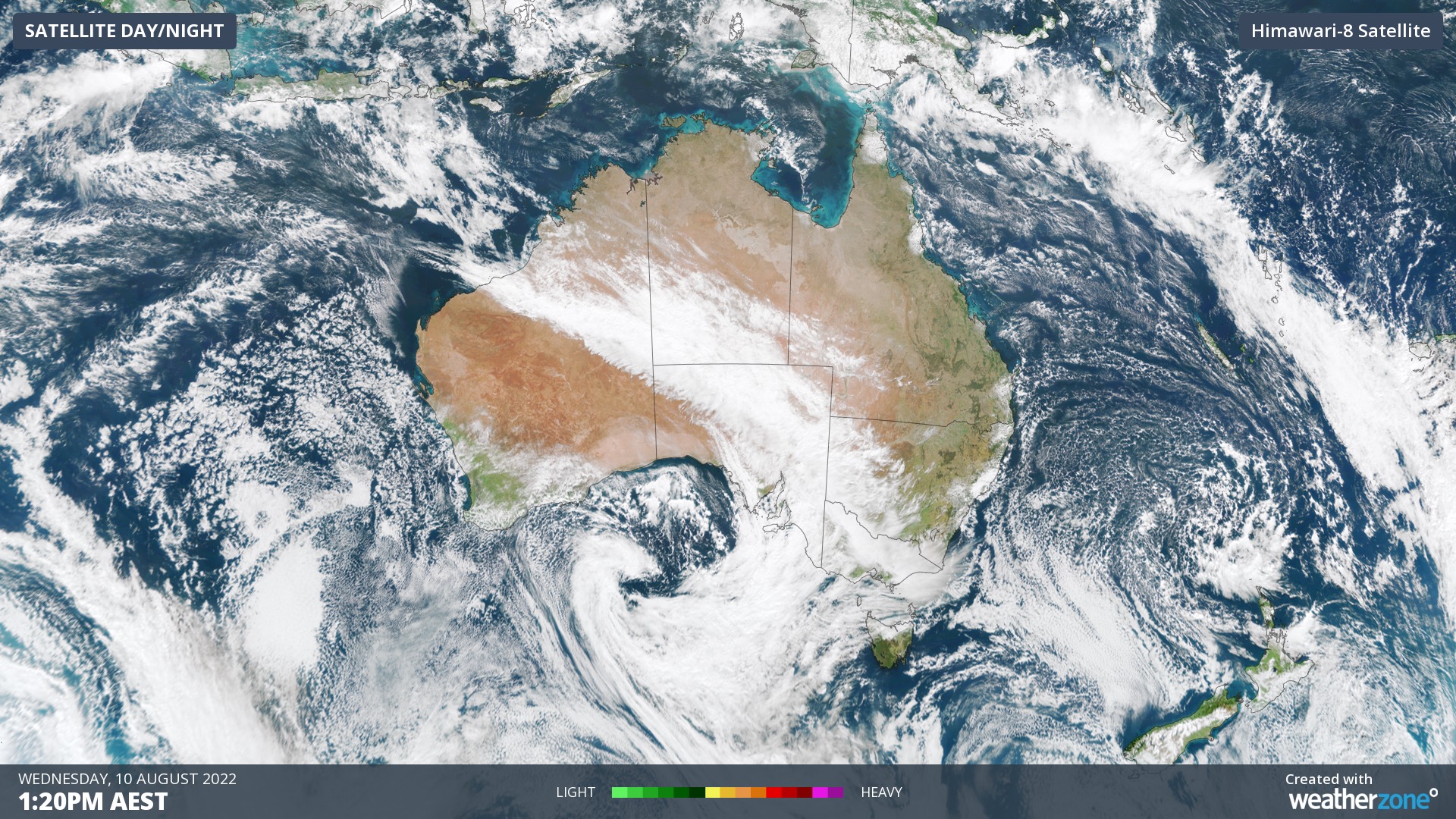

Image: A northwest cloudband that brought significant rain and snow to the southeast in August 2022

Models are currently forecasting a shift in 2023 towards a positive IOD (akin to El Niño). In contrast to a negative IOD, positive IOD events cause a build-up of colder waters off the northwest shelf, with higher pressure usually completely stopping any northwest cloudbands from forming.

Typically, this makes winter drier and sunnier than normal, making for warm days but colder nights. The last positive IOD was in 2019, being one of the major climate drivers that year to the infamous Black Summer Bushfires.

How sure are we that a positive IOD will form?

While it currently looks like the most likely scenario, there is a huge caveat to that forecast: the Autumn Predictability Barrier (also known as the Spring Predictability Barrier by the northern hemisphere).

The Autumn Predictability Barrier refers to how climate forecast (including El Niño/La Niña) are notoriously unreliable at this time of year and can change quite dramatically. The reason is that it’s the height of tropical cyclone season for the southern hemisphere.

Tropical Cyclones disperse heat energy in the ocean through the cyclonic winds (clockwise in the southern hemisphere) imparting a spin in the water beneath them. This spin helps to draw colder waters up from deep below the ocean's surface, leading to a trail of cold water in a system’s wake. With one tropical cyclone, an accumulation of warmer waters that may help setup a particular climate driver can be eliminated.

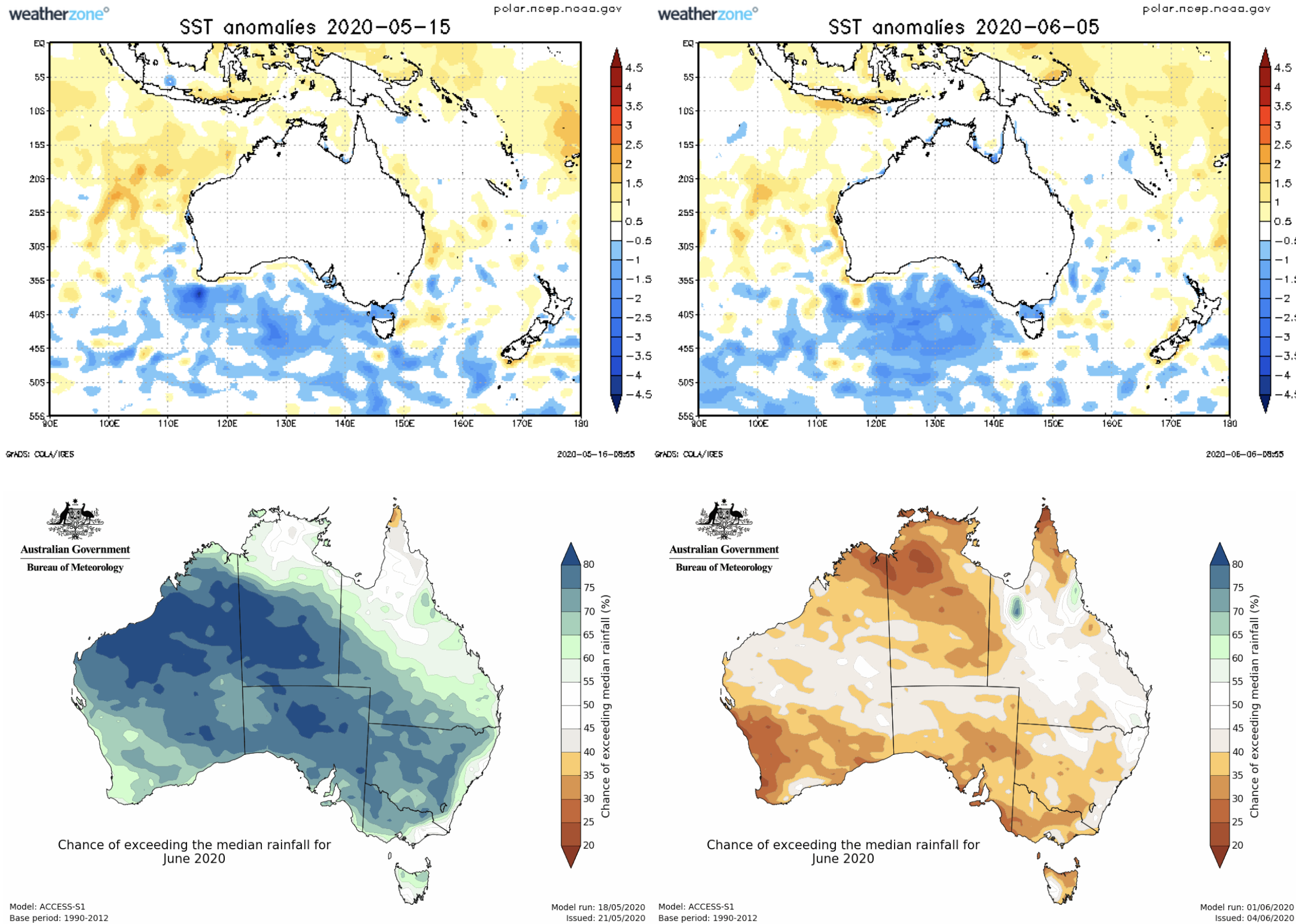

A recent example of this was in May 2020 with Tropical Cyclone Mangga. The climate update on May 21st indicated wetter than average conditions during June for much of the country. After the out-of-season Tropical Cyclone Mangga formed and struck the WA coast during 19-25th May, a cold trail of water had formed near the equator and the northwest shelf. Just 2 weeks after the May update, the climate outlook released on June 4th had completely (and correctly) flipped the rainfall outlook for June 2020.

Image: Sea Surface Temperatures (top) and BoM rainfall outlook (bottom) from before TC Mangga (left) and after (right). The cooling (less orange and a bit of blue) occurring off the northwest shelf reduced the chances of a wet June in 2020.

So, what's the takeaway?

A positive IOD is possible and currently the most likely forecast for winter 2023, but plenty of attention will be paid to how the remainder of the tropical cyclone season plays out.