Nature’s air conditioner: how the seabreeze will help Sydney cope during the heatwave

As heatwave conditions take hold of southeastern Australia this weekend, the cooling seabreeze will be crucial in easing daytime heat, but how does it form?

During periods with weak synoptic forcing, with a broad high pressure system moving slowly over the Tasman Sea, the seabreeze circulation dominates, as we can see below.

Image: Australia’s synoptic situation this weekend, with a broad high pressure system lying over the lower Tasman Sea, bringing light synoptic winds to eastern NSW.

Image: Australia’s synoptic situation this weekend, with a broad high pressure system lying over the lower Tasman Sea, bringing light synoptic winds to eastern NSW.

As the sun rises through the mid-to-late morning, the land can quickly heat up 3-6 degrees warmer than the ocean temperatures (which currently sit between 18 and 23 degrees off the NSW coast). The extra land heating leads to a relative low pressure area over land, and high pressure offshore. Winds move from high to low pressure attempting to even this pressure difference, leading to the onset of the seabreeze with winds turning onshore (blowing from the sea onto land).

Figure: The onset of the seabreeze through the morning as land heats more rapidly than the ocean. Source: annotated figure from Google Earth

Figure: The onset of the seabreeze through the morning as land heats more rapidly than the ocean. Source: annotated figure from Google Earth

As the maximum heating occurs around the middle of the day, the temperature difference between land and sea reaches its peak, and so does the seabreeze. The strength of the seabreeze will dictate how far inland the cooler and more humid winds reach – which is called the seabreeze front. Convection often occurs along this front, with anything from small cumulus cloud with no rain, to towering cumulonimbus thunderstorm cloud, depending on the environment the front pushes into.

Figure: The seabreeze reaches maximum strength through the afternoon following the maximum heating period of the day. Source: annotated figure from Google Earth

Figure: The seabreeze reaches maximum strength through the afternoon following the maximum heating period of the day. Source: annotated figure from Google Earth

Loop of the seabreeze front pushing inland over Western Australia’s Pilbara, with convective clouds forming as the front moves inland. More intense convection and thunderstorms can be seen across the Dampier Peninsula (top right) as seabreeze’s from both sides of the peninsula collide.

Loop of the seabreeze front pushing inland over Western Australia’s Pilbara, with convective clouds forming as the front moves inland. More intense convection and thunderstorms can be seen across the Dampier Peninsula (top right) as seabreeze’s from both sides of the peninsula collide.

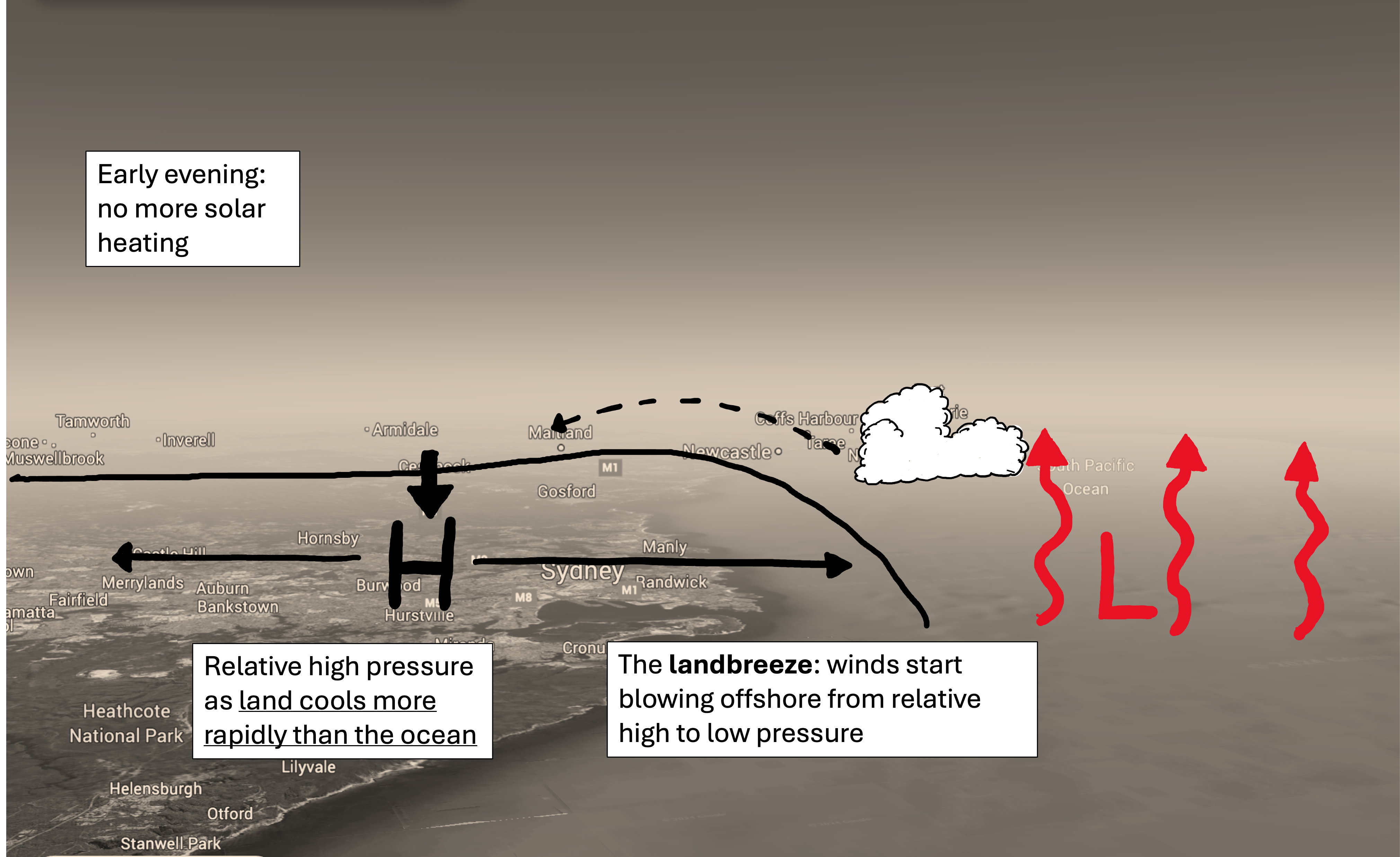

As the sun dips closer to the horizon, heating subsides and the seabreeze circulation slowly weakens, subsiding completely a couple hours after sunset. The land then cools much quicker than the ocean, leading to a reversal of the seabreeze process. Relative low pressure is found offshore over the warmer ocean, and relative high pressure over land, sending winds from land to sea, forming the landbreeze.

Figure: The landbreeze forms after solar heating eases, allowing the land to cool much quicker than the ocean. Source: annotated figure from Google Earth

Figure: The landbreeze forms after solar heating eases, allowing the land to cool much quicker than the ocean. Source: annotated figure from Google Earth

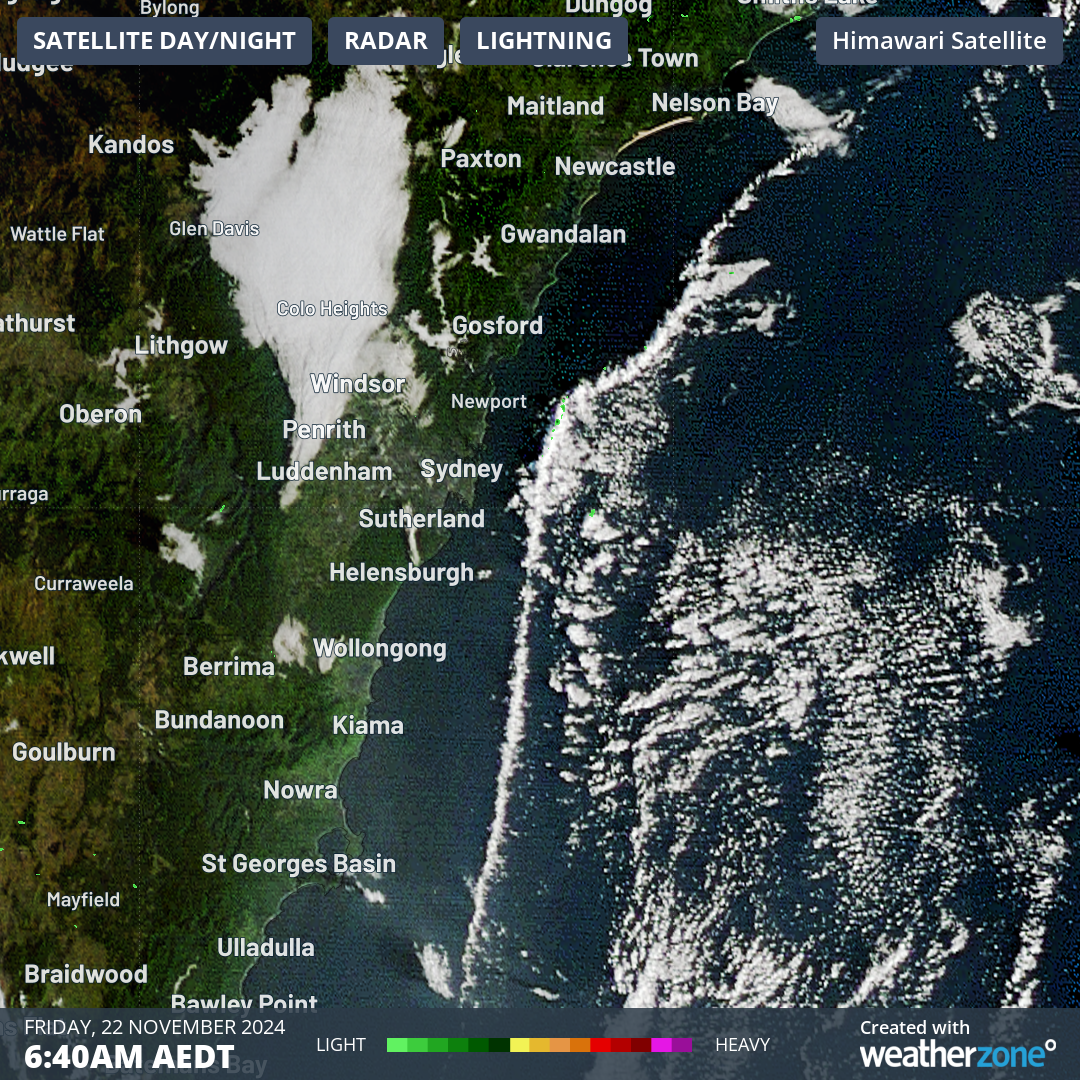

Over the warm waters off the NSW coast, this landbreeze often leads to nocturnal convection with late evening thunderstorms forming offshore. A line of clouds can also be found parallel to the coast the following morning, associated with the decaying remains of the landbreeze, before the whole process is repeated.

Image: satellite imagery showing a line of clouds parallel to the NSW coast between Seal Rocks and Ulladulla, nearly 400 kilometres long, associated with the overnight landbreeze.

Image: satellite imagery showing a line of clouds parallel to the NSW coast between Seal Rocks and Ulladulla, nearly 400 kilometres long, associated with the overnight landbreeze.

Image: The sun rises behind the remaining landbreeze front convection off the Sydney coast.

Image: The sun rises behind the remaining landbreeze front convection off the Sydney coast.

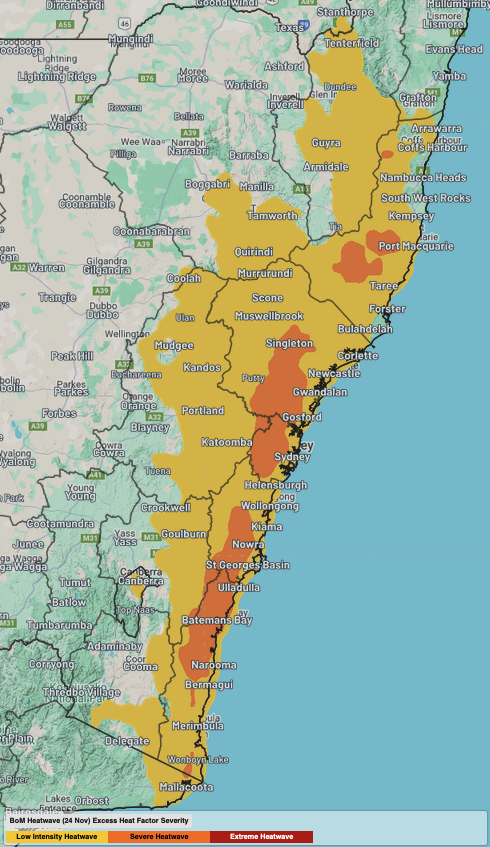

As a pre-summer heatwave impacts southeastern Australia, the seabreeze will play a crucial role in determining the maximum temperatures reached over the coming days in NSW. Seabreezes are expected to form over much of the NSW and Sydney coast during the coming bout of heat, preventing the worst of the heat from reaching coastal NSW. However, a significant temperature gradient will be evident moving away from the coast.

Image: low intensity to severe heatwave conditions forecast for much of eastern NSW between Monday, November 25, and Wednesday, November 27.

Image: low intensity to severe heatwave conditions forecast for much of eastern NSW between Monday, November 25, and Wednesday, November 27.

For example, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sydney’s warmest days this week, temperatures will be in the high-20s along the coastal fringe, in the low-30s across the CBD and more central suburbs, and should reach the mid-to-high-30s across the western suburbs. The daily seabreezes will also pump humidity into eastern NSW, making it feel 2-3 degrees warmer than actual, and leading to little relief overnight by keeping nights very warm.